Managing Editor

For those who’ve never visited Cooperstown, New York, you are missing a genuine slice of history at a site revered for its devotion to the American pastime.

On a hot summer day in August 1964, my father loaded myself and my brother Doug and our family friend Bill Topham in his 1962 Chevrolet Impala and we headed east on the New York State Thruway from our home in Rochester for a trip to the National Baseball Hall of Fame and Museum in Cooperstown. It was about a three-hour drive and my mom had packed us a picnic basket filled with baloney sandwiches, Coca Cola, grapes, and potato chips.

Bill was a World War I veteran who was a lifelong baseball fan but like us, he had never been to the Hall of Fame. My father told us that he had visited there once in 1946 when he was on his way from Rochester to attend Manhattan College in New York City upon his discharge from the U.S. Army following World War II.

I was fascinated listening to Bill’s stories of the early days of baseball in Rochester, especially when he told us about the Rochester Red Wings’ exceptional team of 1929, while playing in the International League that season under two managers, Bill McKechnie and Billy Southworth, and opening a new stadium in the city that same year. He described how Southworth came to be the Red Wings’ skipper in 1929 after being promoted to manage the St. Louis Cardinals in the major leagues that spring.

A former outfielder who played for St. Louis when it won the World Series in 1926, Southworth decided to impose new rules for discipline on the 1929 Cardinals that forbid them from driving a car, and the players rebelled. After just 88 games, McKechnie, who had been managing the Cardinals before Southworth and had replaced him as the Red Wings’ manager, was elevated back to his old managerial job, and Southworth was demoted back to managing Rochester in the minor leagues. Southworth proceeded to guide Rochester to four consecutive International League championships and cemented his place in Rochester lore forever.

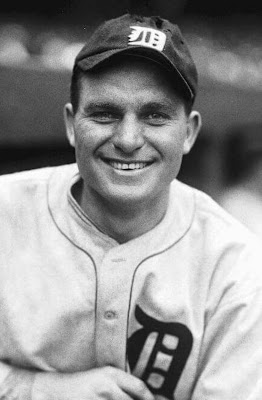

My dad mentioned that he wanted to see Lou Gehrig’s #4 New York Yankees’ uniform which he wore when he made his famous “Luckiest Man” speech upon his retirement on July 4, 1939. Bill said he wanted to see the new plaques that had just been installed the month before for 1964 Hall of Fame inductees Burleigh Grimes, Luke Appling, Red Faber, Miller Huggins, and especially Heinie Manush, whom he said had dated his wife Ida long before they were married. (Apparently Ida liked sports stars because she also once showed me an old black and white photograph of her on a date with heavyweight boxing champion Max Baer, Sr.)

We finally arrived in Cooperstown, parked, and entered the Hall of Fame just before noon. Bill began to laugh and called us over to look at the Hall of Fame plaque for Bill McKechnie, who had been inducted two years prior to our visit in 1962. When I looked at the plaque to the immediate left of McKechnie, I was amazed to see one for Jackie Robinson, who had become the first African American player of the 20th century in 1947. To McKechnie’s right was the great Cleveland Indians right-handed pitcher Bob Feller, who had won 266 games during his major league career and pitched three no-hitters. Billy Southworth was also elected to the Hall of Fame as well in 2008.

Our group then walked down an aisle where photographs of the pitchers and baseballs from each major league no-hit games were enshrined. I stopped to read about Bo Belinsky’s no hitter of May 5, 1962, while pitching for the Los Angeles Angels against my favorite team, the Baltimore Orioles. In a shoebox under my bed at home, I had Belinsky’s 1962 Topps baseball card. I also stopped and read the descriptions of the latest two no-hitters in the majors at that time, one thrown by Sandy Koufax of the Dodgers against the Philadelphia Phillies on June 4, 1964, and another thrown by Jim Bunning of the Phillies against the New York Mets on June 21, 1964. I found it interesting that former Orioles’ catcher Gus Triandos caught Bunning’s no-hitter in that game, and I had his 1964 baseball card too.

I joined my dad as he admired a display containing a bat that Babe Ruth of the New York Yankees is said to have used while clubbing his famous "called shot" in the third game of the 1932 World Series against the Chicago Cubs, and next to it was a baseball that he hit for his final career home run, number 714, on May 25, 1935.

We spent more than four hours there and each of us came away with such a wonderful appreciation of the sport. I haven’t been back since but wonder what treasures I would find if I’m lucky enough to return some day.<

No comments:

Post a Comment